So Long Dad

Eric Heiman is a principal and co-founder of the celebrated design studio Volume Inc. He also teaches at the California College of the Arts (CCA), where he co-created and currently manages TBD*, a student-staffed design studio creating work to help local Bay Area nonprofits and civic institutions. Eric also writes about design and culture, is an AIGA Fellow, and has way too many vinyl records.

He has been a friend of and guest on the podcast for the longest time. He joined us recently to discuss Light Years by James Salter. Listen or watch.

Life divides itself with scars, like the rings contained within a tree.

—Light Years

When I manage to ride our makeshift stationary bike—a reappropriated old Specialized Stumpjumper propped up on a stand in the back of our apartment—I, like so many others, listen to music. Usually, an endless playlist, augmented by the streaming algorithm that gives me both what I want and what I might want to hear. The repetition in this routine allows me to focus on the details of each song more than usual, a distraction from the exertion which, in the moment, I loathe. Pedaling to nowhere. (There’s a metaphor in there somewhere.)

My advanced age also requires a stretch and strength training cool-down afterward. I used to enjoy physical fitness when I was younger; my body was more limber and resistant to injury. Now, when I need it the most, exercise is anathema. My favorite part is the pause between reps, on my back, when my mind often drifts to the melody in my earbuds, and associative mental boomerangs spin into orbit.

During one of these respites, “Wandering Boy” by Randy Newman came on. Lyrically, it’s a father going about his everyday life of work and friends, then pining for his wayward, lost son:

Where is my wandering boy tonight?

Where is my wandering boy?

If you see him tell him everything’s alright

Push him toward the light

Where is my wandering boy?

Newman is most known for his Pixar soundtrack music (“I’ve Got a Friend in You”), a wry and often misunderstood anthem for the City of Angels (“I Love L.A.”), and the caustic and probably-verboten-in-2025 anti-ode to the diminutive (“Short People”). These, unfortunately, eclipse a songwriter so adept at wrapping idiosyncratic personal and political narratives in loping, lilting music that would burrow into your soul even if you didn’t understand English.

And so, horizontal on the carpet, sweat drying on my forehead, staring up at our painted wood-lath ceiling, I heard this chorus, and a lump ballooned in my throat. I sobbed.

────────────

My first memory of Randy Newman is the cover of his 1977 LP, Little Criminals. (The one with “Short People”.) It was scattered amongst my father’s bebop jazz records that sat haphazardly shelved by his hi-fi setup in the West Hill apartment he rented after my parents’ separation and eventual divorce. The sleeve art sticks in my mind because the black and white image of Newman—standing on a bridge over a Los Angeles freeway, wearing a sports jacket and cool shades, curly hair blowing in the SoCal breeze—looked like my dad.

Years later, on one of many shared-custody weekends, we were watching a late-night mix of sketch comedy shows, classic movies, and interstitial music video showcases like “Night Flight” when the hypnotically goofy “I Love L.A.” video came on, with Newman in a Hawaiian shirt and driving a convertible “with a big nasty redhead by [his] side.” The song’s subversive commentary was above my western Pennsylvania tweener’s head, but the same thought occurred—this guy is like my dad. I later bought the album (Trouble in Paradise, 1983) with birthday money. But between its bad eighties production and mature themes, I quickly forgot it, as my emerging adolescent musical tastes demanded soundtracks with more visceral teen angst and less synth piano.

────────────

At the Pennsylvania college I attended, there was a small venue—Studio Theater—where drama students could stage their own original performances, free from the glitz of the more marquee plays and musicals put on in the larger campus theater. On an early date with an early love, we went to an ad-hoc revue of Randy Newman songs produced by some of the drama school sophomores and juniors. I’ll never forget the compact Ty Taylor, dressed in only jeans rolled up to the mid-shin, leaping onto the armrests of a seat in the front row (we were in the second), and with a demonically wide smile, start taunting us with the refrain of “Pants” (Born Again, 1979)—Gonna do it right now / I’m gonna take off my pants.

But it was watching all these formidable performers (a few would go on to win Tony awards, one just this year) take on songs I had never heard before—“Burn On”, “Political Science”, “Dayton, Ohio-1903”, “Lonely at the Top”, and a slinky version of “You Can Leave Your Hat On”—that led me to Newman’s 1972 release, Sail Away.

There isn’t a bad song on the record, but it was a lesser-known track, “Memo to My Son,” that jumped out:

I know you don’t think much of me

Someday you’ll understand

Wait’ll you learn how to talk, baby

I’ll show you how smart I am

Wanna show you how smart I am

The song is short, and fits nicely at the end of a mixtape side. I still have one where it concludes Side A, and I still speak to the early love occasionally.

────────────

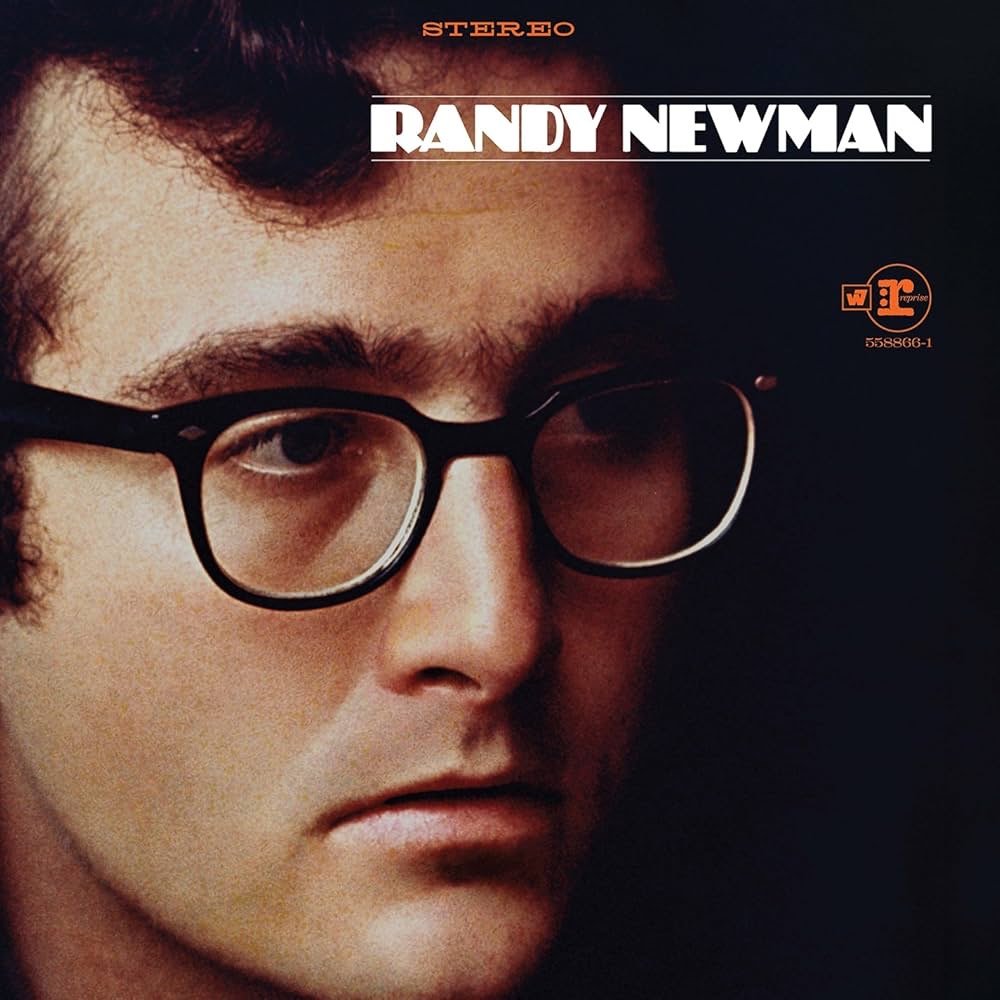

In the mid-1990s, Newman did a short performance and signing at the Union Square Border’s to celebrate the CD release of a part of his back catalog never converted to digital formats. My friend Bryan, always attuned to the local music events, suggested we go. There was a modest crowd, and Newman, with graying, still-unruly hair at a baby grand piano, played a few songs across his almost three-decade-old discography, colored with self-deprecating wit in between. I bought both his first self-titled album (1968) and Live (1971—neither of which I had ever heard) and dutifully got in line with Bryan to get them signed.

When our turn was up, Newman looked at us and chuckled, “You two are probably the youngest people here. Did you come with your parents?” We laughed, too, and I remarked that indeed, yes, it was my father who introduced me to his music.

“Well, your dad must be a cool cat.”

He signed the CD booklet of the self-titled album with a couplet from “Political Science” I asked for. Then he paused to ponder the front cover, a gauzy close-up portrait.

“Look at this guy. So young and stupid.”

Look at this guy. He still looks like my dad.

Randy Newman’s S/T LP cover

────────────

After my grandmother died, I helped Dad and Uncle Rick clear out my grandparents’ house. (My grandfather had died only a few months prior.) They were ruthlessly unsentimental and didn’t keep much. This place was the only consistent “home” of my peripatetic life up to that point. I wanted to save the smells—the worn leather couch and chairs of the family room, the chicken soup waft from the kitchen on Friday night Shabbat dinner–but I settled for two framed black and white photos, one of my father, one of my uncle, taken seconds apart at my parents’ first house, before I was even born. They face each other on a wall in our apartment now, having a silent conversation. With his horn-rimmed glasses, my father looks eerily like Newman on the self-titled LP I had Newman sign years before.

Uncle Rick and Dad

────────────

One of the tracks on Live is a version of the 12 Songs (1970) track, “Old Kentucky Home,” an anti-romantic take on the bucolic southern state through the eyes of a backwoods family. Evan was from Lexington, and when I first played this song for him, he howled, maybe in partial recognition and surely in Kentucky pride, even as a proud San Francisco transplant. He died some years later at 32, after a marathon-training run. Evan had an enlarged heart condition that he kept secret from all of us. There’s a strange, sad poetry in that. When “Old Kentucky Home” comes on, I always think of him and that laugh.

────────────

Our friend Julie used to work for Warner Records, and Newman was one of the artists in her roster. When she left the company, she was clearing out her desk and sent me a signed copy of Newman’s handwritten “Wandering Boy” lyrics that she found. I still haven’t framed it.

────────────

During the pandemic, Newman wrote and recorded a song called “Stay Away”—

Stay away from me

Wash your hands, but don’t touch your face

(How do you like that?)

Wash your hands

Don’t touch your face, I saw you

You could download it with a small donation to Ellis Marsalis’ Music School in New Orleans. (Also the city where my dad went to college.) I know I made the purchase, but currently can’t find it in my music library. You can stream it now on most platforms, but seek out the YouTube video with Newman hunched over the piano, singing to his wife, who is recording him on her iPhone.

────────────

Come and see us, Papa, when you can

There’ll always be a place for my old man

Just drop by when it’s convenient to

Be sure and call before you do

—“So Long Dad” (1968)

I still have an analog sound system—turntable, dual cassette deck, CD player, speakers—and my only concession to the streaming age is a discontinued Apple AirPort Express that allows me to pull streaming music into the setup. I rarely do.

When we went through my father’s possessions, I found old mixtapes and CDs I had made for his birthday or Hanukkah over the last three-plus decades. I always designed custom sleeve art to go with them, and my favorite, which he still had, was the Heiman Ah-Hum CD based on one of his favorite albums, Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah-Um.

Grieving is a protracted, neverending process. Making music mixes started with the urge to assuage the roil of youthful emotions that were so hard to wrangle. In hindsight, the endings they commemorated—of time periods, of relationships—still seemed ephemeral and unfinished then. Still available for a rewrite. Now, similar moments have an existential finality no soundtrack can undo. I made more than 12 CD mixes in honor of Evan after he died. They were effective medicine for a time, but their effect quickly wore off. Every time I hear the Lemonheads version of “Frank Mills,” I usually tear up. 32 is too young to die.

When I returned home, I dug up an old blank Maxell 90-minute cassette and, in honor of my father, made an analog mixtape of songs that reminded me of him. I gathered the records and CDs of the songs I might include. I sat by the stereo, and one by one, started and stopped the recording with the Pause button of the tape deck, listening through every second of every track. I hadn’t done that in over a decade, maybe two.

The mix is called “So Long Dad,” and the last song on side B—“Rollin’” (Good Old Boys, 1974)—is by Newman.

Every evening what I do

Is I sit here in this chair

Pour myself some whiskey

Watch my troubles vanish into the air

Rollin’, rollin’

Ain’t gonna worry no more

Rollin’, rollin’

Ain’t gonna worry no more

────────────

Randy Newman is suddenly everywhere. The benefit concert for the recent Eaton fires in Los Angeles was called “I Love L.A.,” and the song was performed later on the Grammy Awards. He was a musical guest on John Mulaney’s live Netflix show. When we saw his recent cameo on Hacks, Megan sighed and said, “Wow, he reminds me so much of your dad.”

────────────

Life is an inevitable march. And a rich, rich mosaic.

────────────

It happens in an instant. It is all one day, one endless afternoon, friends leave, we stand on the shore.

—Light Years

(Ronald T. Heiman, 1942–2023)