Fiction, History, and the Truth Buried in the Banana Massacre

La novela latinoamericana es en general un documento mas exacto que la historia.

German Arciniegas

Colombian historian, writer, and journalist

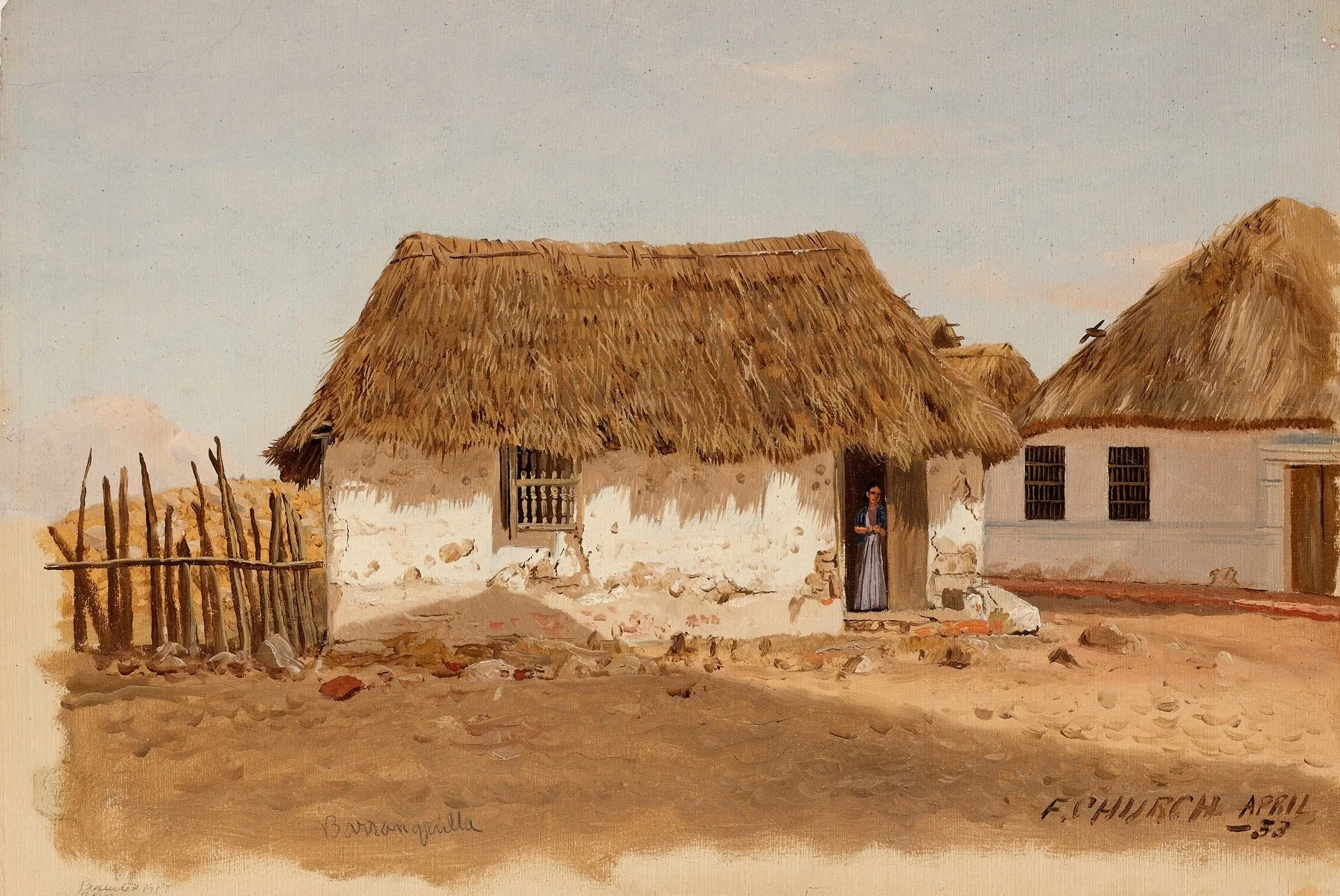

Two Houses in Barranquilla, Colombia (1853), Frederic Edwin Church—Source

Rumors in Gabriel García Márquez’s childhood

Stories traveled quickly down those dusty roads, alighting unexpectedly like aracari on crumbling courtyard fountains. They passed from hand to hand among banana pickers. They whispered from the lips of old men with wrinkled leathery faces, who wore high-waisted trousers and who leaned on wooden canes in the shade of the tree-lined plaza.

A thousand people, I heard.

I heard it was two thousand.

The Banded Aracari Toucan — Source

It was early December 1928 on the sweltering coast of Colombia. The children were already giddy with excitement for Día de las Velitas (the Day of the Little Candles), a colorful display of illuminated lanterns celebrating the Virgin Mary’s Immaculate Conception. Beyond that, tantalizingly close, if you counted with your fingers and your toes, was la Nochebuena (Christmas Eve) and the exchanging of gifts.

Little Gabo was not yet two years old, tottering around in a sunny courtyard of a quiet,colonial-style home in Aracataca. A thick, warm breeze would be blowing through the glassless windows. He would be learning to stack simple words together. Más pan. Abuelo duerme. Pájaro canta. He didn’t know it, but he was opening his eyes to the myths, characters, and landscapes that would populate his fiction and haunt the imagination of readers far beyond his lowland Caribbean hometown.

Reports of an historical massacre in a fictional world

Leaders of the banana plantation workers’ strike — Source

In Ciénaga, merely twenty miles from Aracataca, the Colombian army opened fire on striking workers of the United Fruit Company. Somewhere between twelve and two thousand people are believed to have been killed. To this day, the exact number of dead remains unknown, buried by corruption, complicity, and time. Yet, while history could not recover the atrocities of the Banana Massacre in full, the tragedy would likely have been told and retold by his grandfather, Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía, a veteran of the Thousand Days’ War and a vocal critic of the government. The event would galvanize Gabriel García Márquez.

In an interview in 1990, he said:

The banana events are perhaps my earliest memory… There was a talk of a massacre, an apocalyptic massacre.

Years later, he awakened these tragedies from the grave and gave them a new life in the pages of his masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude.

The captain gave the order to fire and fourteen machine guns answered at once. But it all seemed like a farce...when Jose Arcadio Segundo came to he was lying face up in the darkness. He realized that he was riding on an endless and silent train and that his head was caked with dry blood and that all his bones ached...in the flashes of light that broke through the wooden slats as they went through sleeping towns he saw the man corpses, woman corpses, child corpses who would be thrown into the sea like rejected bananas.

Fiction, however, is not a substitute for history. The ghosts it conjures are convincing illusions, while history is a slow-moving train. Onboard are wise and learned people who are perpetually disembarking to deliver an update on the facts, to place a long-awaited period on a runaway sentence.

Myth, language, and memory in Macondo

The first time that I read the novel, over a decade ago, I was captivated by the lush world that Márquez creates. Its magical qualities, both whimsical and earnest, seemed not mere fantasy, but an expression of something deeply true. Like most of the world before this novel was published, I had not heard of the real life Banana Massacre. The event depicted on those pages seemed to me something more general—a vague idea about the evils of foreign capitalist exploitation of vulnerable and naive native populations. Yet this did not diminish the power of the novel. The massacre—although it may represent the violent climax of the story, the ultimate loss of innocence, and the beginning of the end for the town of Macondo—is not the most powerful image (although it is perhaps the most widely discussed one).

First edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude — Source

The imagery that Márquez invokes elevates each little moment to the same domain of myth occupied by the popular legend of the Banana Massacre. Yet he writes with the straight-face of a journalist dutifully reporting the facts. Consider, for example, the rain of flowers upon the death of the patriarch José Arcadio.

...through the window they saw a light rain of tiny yellow flowers falling. They fell on the town all through the night in a silent storm, and they covered the roofs and blocked the doors and smothered the animals who slept outdoors. So many flowers fell from the sky that in the morning the streets were carpeted with a compact cushion and they had to clear them away with shovels and rakes so that the funeral procession could pass by.

Each of these moments, magical and mundane, feels as real as every other, from the mystery of ice—“the sunset was broken up into colored stars”—and magnets—“the desperation of nails and screws trying to emerge” to the civil war, to the ascension of Remedios the beauty, to the seventeen Aurelianos all marked with ash, and, of course, to the massacre of the striking banana workers in the town square.

Meaning, alchemy, and Wittgenstein

The American author and contemporary of Márquez, James Salter, wrote in the epigraph for his final novel, All That Is, that “everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.” This is true of both fiction and history. Although one purports to deal in fact, and the other illusion, what we crave from each is often the same. Like alchemists, we pursue in the ordering of the nouns, the verbs, the subjects, and the objects a sort of Philosopher’s Stone, a revelation of an ordered reality to unite the multifarious and conflicting sensations we accumulate over a lifetime. Abuelo duerme, we say. Perhaps, we haven’t gotten so far from our first words.

From the Manly Palmer Hall collection of alchemical manuscripts, 1500-1825 — Source

Early in the novel, Solitude addresses this same concept directly, but Márquez takes it a step further than Salter. When the residents of Macondo become infected by an insomnia plague, they begin losing their memory. As a solution, they label everything with its name and a description of its function. Ultimately, however, this proves insufficient.

Little by little, studying the infinite possibilities of a loss of memory, he realized that the day would come when things would be recognized by their inscriptions but that no one would remember their use.

And later…

Thus they went on living in a reality that was slipping away, momentarily captured by words, but which would escape irremediably when they forgot the values of the written letters.

The significance of words, Márquez informs us, does not reside merely in their relation to the objects they signify. If that is the case, something crucial will have been lost. All of Jose Arcadios’ attempts to cobble together a scaffold to reconstruct meaning results in nothing but “somber nonsense.” Rather, it is the resurrected Melquíades, the wandering gypsy, who, with a “drink of a gentle color” (the Elixir of Life perhaps) ultimately delivers him from his forgetfulness.

I hear echoes of the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in this episode, when he proclaims in his Philosophical Investigations(§43): “The meaning of a word is its use in the language” (emphasis mine). In Macondo, as in our world, when memory and context are lost, meaning dissolves—even if the label remains.

Revelation

In exquisite prose, Márquez answers the question that must have agonized many families that December in 1928. Why were so many people absent on la Nochebuena that winter?

For the socially minded reader, his answer, embodied not just in historical allegory, but in the broken, haunted figure of José Arcadio Segundo, has the sickly-sweet flavor of hidden knowledge. The feeling of discovering something that you are not supposed to find: three thousand innocent victims murdered and dumped into the sea. But as Márquez would clarify in the same 1990 interview, this claim isn’t factually accurate.

...there can’t have been many deaths. But even three or five deaths in those circumstances at that time...would have been a great catastrophe.

Rainy Season in the Tropics (1866) by Frederic Edwin Church — Source

Indeed, the novel hints at its own unreliability for José Arcadio Segundo is, like many characters in the novel, obsessed and delusional. He repeats until his final days “¡Fueron más de tres mil!” Yet no one believes him. His experience in the protest, far from leading the people of Macondo to the truth, becomes a lonely burden that isolates him from the world as he retreats further and further into silence.

“There haven’t been any dead here,” she said. “Since the time of your uncle, the colonel, nothing has happened in Macondo.”

“You must have been dreaming,” the officers insisted. “Nothing has happened in Macondo, nothing has ever happened, and nothing ever will happen. This is a happy town.”

The official version, repeated a thousand times and mangled out all over the country by every means of communication the government found at hand, was finally accepted: there were no dead, the satisfied workers had gone back to their families...

The result of the massacre within the story is the prevalence of ignorance and cruelty. The reader feels the implicit allegation of bearing silent witness to a tragic erasure (or even worse, becoming a passive accomplice for enjoying a Chiquita banana at breakfast). Were this to be the sum total of Solitude, it would be a bleak tale.

Upon this point the novel teeters, balancing tragedy and beauty, guilt and ecstasy to achieve what filmmaker Werner Herzog termed in his polemic Minnesota Declaration “ecstatic truth.” Through imagination and style, Márquez shapes a quantifiable but elusive fact into a deeper and even more elusive reality.

Babylon the great is fallen, is fallen… for in one hour so great riches is come to nought.

Revelation 18:2, 18:17

The destruction of the Buendia clan and of Macondo itself are fated from the very first days. Melquíades’s nearly indecipherable manuscript, like the psychedelic Revelations of John, tantalizes multiple generations with the hope that, with sufficient study and the proper decryption, the worst might be avoided. In the end, however, understanding and destruction are intertwined in this esoteric text, suggesting that foreknowledge is an illusion and scholarship is merely a way to pass the days.

...it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering the parchments...

In this way Márquez wraps up his story—every pursuit comes to nothing, knowledge cannot divide itself cleanly from the flow of events, and history cannot forestall fate. Yet Márquez offers the reader a glimmer of hope, a redemption of another order.

The answer he seems to propose again and again, throughout the story, is that the meaning of life is not the sum of accumulated facts. The truth about the Banana Massacre is not to be found in a number between 3 and 3,000. There is no fixed value beyond those two parallel horizons at the end of the long equation of life to make sense of all that came before.

Rather, value lies in the art of the telling. Words may be arranged to reflect a shared, verifiable reality, or to resonate within a silent and solitary chamber. Properly understood, they do not serve merely to illuminate a distant, redemptive fact; they lift off the page like sheets billowing in the wind. They rain down like a storm of yellow flower blossoms. They make us forget, if for a moment, that we were ever looking for anything more.